We’re taking a look back at some of our favourite and most popular Entertainment stories of 2024, giving you a chance to catch up on some of the great reading you might have missed this year.

In this story from September, we take a look back at the life of Kris Kristofferson, who wrote songs for hundreds of other artists, including Me and Bobby McGee for Janis Joplin and Sunday Morning Coming Down for Johnny Cash, before a second

act in film.

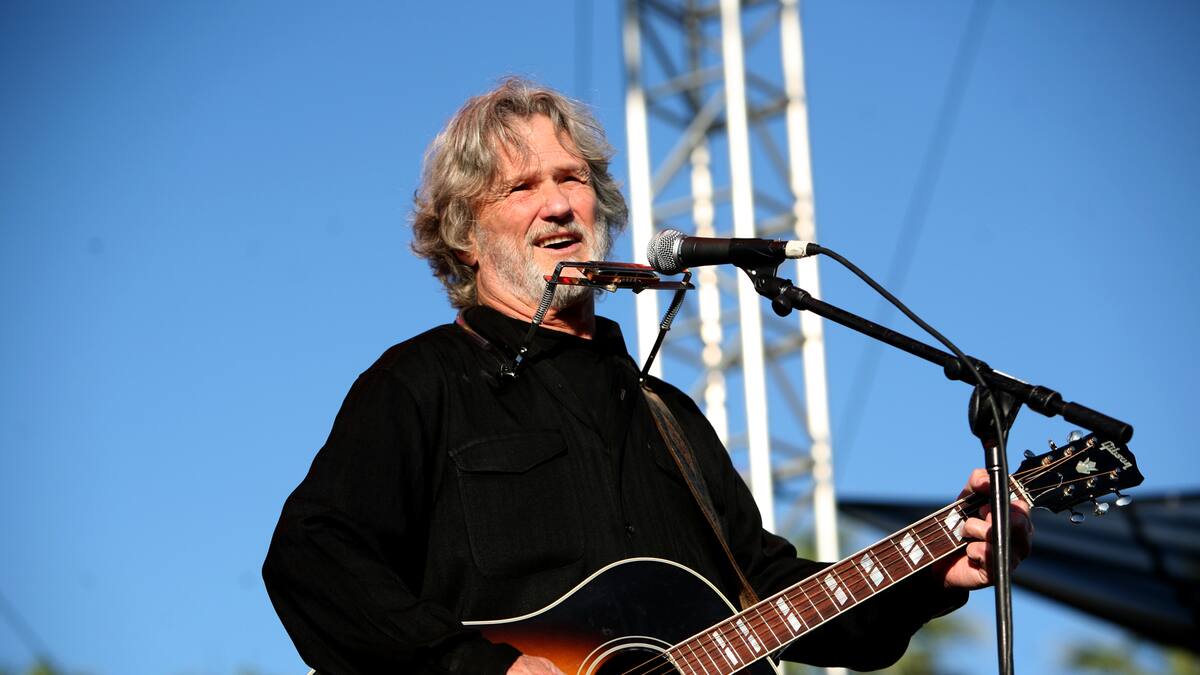

Kris Kristofferson, a singer-songwriter whose literary yet plain-spoken compositions infused country music with rarely heard candour and depth, and who later had a successful second career in movies, died at his home on Maui, Hawaii in September at the age of 88.

His death was announced by Ebie McFarland, a spokesperson, who did not give a cause.

Hundreds of artists have recorded Kristofferson’s songs – among them Al Green, the Grateful Dead, Michael Bublé and Gladys Knight and the Pips.

Kristofferson’s breakthrough as a songwriter came with For the Good Times, a bittersweet ballad that topped the country chart and reached the Top 40 on the pop chart for Ray Price in 1970. His Sunday Morning Coming Down became a No 1 country hit for his friend and mentor Johnny Cash later that year.

Cash memorably intoned the song’s indelible opening couplet:

Well, I woke up Sunday morning

With no way to hold my head that didn’t hurt

And the beer I had for breakfast wasn’t bad

So I had one more for dessert.

Expressing more than just the malaise of someone suffering from a hangover, Sunday Morning Coming Down gives voice to feelings of spiritual abandonment that border on the absolute. “Nothing short of dying” is the way the chorus describes the desolation that the song’s protagonist is experiencing.

Steeped in a neo-romantic sensibility that owed as much to John Keats as to the Beat Generation and Bob Dylan, Kristofferson’s work explored themes of freedom and commitment, alienation and desire, darkness and light.

“Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose/Nothin’ ain’t worth nothin’ but it’s free,” he wrote in Me and Bobby McGee. Janis Joplin, with whom Kristofferson was briefly involved romantically, had a posthumous No 1 single with her plaintive recording of the song in 1971.

Later that year Help Me Make It Through the Night became a No 1 country and Top 10 pop hit in a heart-stopping performance by Sammi Smith. The composition won Kristofferson a Grammy Award for Country Song of the Year in 1972.

It was a heady time to be a songwriter in Nashville, Tennessee, where Kristofferson fell in with a gifted circle of like-minded – and similarly bacchanalian – tunesmiths who were as driven to succeed as he was, Roger Miller and Willie Nelson among them.

“We took it seriously enough to think that our work was important, to think that what we were creating would mean something in the big picture,” Kristofferson said in an interview with the journal No Depression in 2006.

“Looking back on it, I feel like it was kind of our Paris in the ‘20s,” he went on, alluding to American expatriate writers like Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein who lived there at the time. “Real creative and real exciting – and intense.”

Kristofferson’s own raspy, at times pitch-indifferent vocals never quite gained traction with commercial radio. One notable exception was the gospel-suffused Why Me, a No 1 country and Top 40 pop hit released on the Monument label in 1973. (Another gospel song of his, One Day at a Time, written with Marijohn Wilkin, was a No 1 country single for singer Christy Lane in 1980.)

Kristofferson and Rita Coolidge, who were married for much of the ‘70s, won Grammy Awards for best country vocal performance by a duo or group with From the Bottle to the Bottom (1973) and Lover Please (1975). They also appeared in movies together, including Sam Peckinpah’s gritty 1973 western, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, in which Kristofferson played the outlaw Billy the Kid. Peckinpah cast Kristofferson in the film after seeing him perform at the Troubadour in Los Angeles and in Cisco Pike (1972), his big-screen debut.

Martin Scorsese then cast Kristofferson, whose rugged good looks lent themselves to the big screen, as the laconic male lead, alongside Ellen Burstyn, in the critically acclaimed 1974 drama Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. He later starred opposite Barbra Streisand in Frank Pierson’s 1976 remake of A Star Is Born, a performance for which he won a Golden Globe Award.

Over four decades Kristofferson acted in more than 50 movies, among them the 1980 box-office failure Heaven’s Gate and John Sayles’ Oscar-nominated 1996 neo-western Lone Star. Singer-songwriters may not be the likeliest of movie stars, but Kristofferson consistently revealed a magnetism and command onscreen that made him an exception to the rule. In 2006 he was inducted into the Texas Film Hall of Fame, along with Matthew McConaughey, Cybill Shepherd and JoBeth Williams.

Kristofferson’s last major hit as a recording artist was The Highwayman, a No 1 country single in 1985 by the Highwaymen, an outlaw-country supergroup that also included his longtime friends Waylon Jennings, Nelson and Cash.

Cash and his wife, June Carter Cash, had played a pivotal role in Kristofferson’s budding career when they invited him to appear with them at the Newport Folk Festival in 1969.

Kristofferson was still a scuffling songwriter at the time, having worked as a janitor at Columbia Studios in Nashville, where he later recalled emptying ashtrays and wastepaper baskets during the 1966 sessions for Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. Immobilised by stage fright at Newport that night, Kristofferson might have squandered his opportunity had it not been for the encouragement of Carter Cash, who, as her husband recalled in interviews, all but dragged him onstage with them.

The evening proved propitious, exposing Kristofferson to a national audience after he received a highly favourable mention in The New York Times the next day.

“If there was one thing that got my performing career started, that was it right there,” Kristofferson said, reflecting on the experience as quoted in the 2013 book Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, by Michael Streissguth.

Kristoffer Kristofferson was born June 22, 1936, in Brownsville, Texas, the eldest of three children of Mary Ann (Ashbrook) and Lars Henry Kristofferson. His father, a Major General in the Air Force, strongly urged him to pursue a military career.

The family later moved west, and in 1954 Kristofferson graduated from San Mateo High School in Northern California, where he distinguished himself in both academics and athletics. He was subsequently featured as a promising boxer in Sports Illustrated’s Faces in the Crowd series in 1958.

Kristofferson graduated with honours with a degree in literature from Pomona College in Claremont, California, in 1958. He also had prizewinning entries in a collegiate short-story contest sponsored by The Atlantic magazine before being awarded a Rhodes scholarship to study English literature at Oxford.

Under the pseudonym Kris Carson, he made a fruitless bid to become a pop star while there, working with Tony Hatch, the British impresario known for his success with singer Petula Clark.

Kristofferson graduated from Merton College, Oxford, in 1960 and received a commission as a second lieutenant in the US Army. In 1961 he married Frances Beer and was stationed in Germany, where he served as a helicopter pilot.

He attained the rank of Captain in 1965 and received an appointment to teach English at West Point. He ultimately declined the position, trading the comforts it might have afforded for the penury of life as a would-be songwriter in Nashville.

If his wife was crestfallen by the move, his parents were scandalised. For a while they disowned him for throwing away everything he had worked so hard to achieve.

“Not many cats I knew bailed out like I did,” Kristofferson said, talking about this tumultuous period for a 1970 feature in The Times Magazine. “When I made the break I didn’t realise how much I was shocking the folks, because I always thought they knew I was going to be a writer. But I think they thought a writer was a guy in tweeds with a pipe. And I quit and didn’t hear from ‘em for a while.

“I wouldn’t want to go through it again,” he continued, “but it’s part of what I am.”

Success in Nashville initially eluded Kristofferson, and not without reason. According to Wilkin, the first publisher to sign him to a songwriting deal, he had a few things to learn – and unlearn – before he arrived at the distinctive mix of vernacular and sophisticated idioms that became his stock in trade.

“He had been a poet and an English teacher, so his songs were too long and too perfect,” Wilkin said in a 2003 interview with Nashville Scene. “His grammar was too perfect. He had to learn the way people talk.”

Kristofferson’s transformation as a songwriter involved more than merely sprinkling colloquialisms like “ain’t” and “nothin’” in among his lyrics. He also cultivated a keen melodic sensibility, a languid expressiveness that bore little resemblance to the straightforward Hank Williams-derived shuffles he was turning out when he first arrived in Nashville.

“I had to get better,” Kristofferson said in an interview with Nashville Scene, reflecting on the lean years before he broke through as a songwriter. “I was spending every second I could hanging out and writing and bouncing off the heads of other writers.”

He also changed publishers, leaving Wilkin’s Buckhorn Music for Combine Music, owned by producer Fred Foster, who also had the freewheeling likes of Shel Silverstein and Mickey Newbury under contract.

In 1970 Foster issued Kristofferson, Kristofferson’s debut as a recording artist, on his independent label Monument. The album contained versions of several songs that had been hits for other artists, including Me and Bobby McGee, for which Foster was credited as a co-writer. (That song was originally recorded by Roger Miller, who had a Top 20 country hit with it in 1969.)

Kristofferson released other albums, to mixed reviews, in the ‘70s; by decade’s end his career in movies had begun to eclipse his reputation as a singer-songwriter.

The ‘80s and ‘90s saw his music take an activist turn, with lyrics championing social justice and human rights. What About Me, a song from his 1986 album, Repossessed, spoke out against right-wing military aggression in Central America.

Bypass surgery in 1999 slowed Kristofferson down, as did an extended bout with Lyme disease in the decade that followed, but he remained active into his 80s.

Kristofferson was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2004. By that time he had already been elected to the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame (in 1977) and the National Academy of Popular Music’s Songwriters Hall of Fame (in 1985). He also received a lifetime achievement honour at the 2014 Grammy Awards.

Kristofferson is survived by Lisa (Meyers) Kristofferson, his wife of over 40 years, their sons, Jesse, Jody, Johnny and Blake, and a daughter, Kelly Marie; a son, Kris, and daughter, Tracy, from his marriage to Beer; and a daughter, Casey, from his marriage to Coolidge; and seven grandchildren.

A man of prodigious gifts and appetites, Kristofferson struggled early on with what path to pursue among the many that were open to him. In the song The Pilgrim, Chapter 33, he seemed to acknowledge as much, depicting a conflicted figure, much like himself, who took “every wrong direction on his lonely way back home”.

Such self-deprecation notwithstanding, Kristofferson believed that songwriting – certainly a “wrong direction” in the eyes of his family, at least at first – was the means through which he discovered his vocation in life, and by which he achieved celebrity and artistic acclaim.

“I wouldn’t be doing any of it if it weren’t for writing,” he said, looking back on his career, in a 2006 interview with the online magazine Country Standard Time.

“I never would have gotten to make records if I didn’t write. I wouldn’t have gotten to tour without it. And I never would’ve been asked to act in a movie if I hadn’t been known as a writer.”

“Writer” was the occupation listed on Kristofferson’s passport.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Written by: Bill Friskics-Warren

Photographs by: Heidi Schumann

©2024 THE NEW YORK TIMES