We settle on sofas, from where the actor barely moves. He instead remains a remarkably still if slumped presence, his delivery an eventually coherent ramble of many thoughts punctuated by frequent bouts of raucous laughter. He is a man who cannot help but be excellent company, largely because he appears to treat his entire life with enormous incredulity.

The room is filled with trinkets. One wall is filled with guitars; another a TV. There’s a model of Depp as Edward Scissorhands and paraphernalia from Pirates of the Caribbean. It is cluttered but clean. He has a photo of his late friend Hunter S Thompson and a doll of Donald Trump climbing into a cage with the American flag inside it — the “horrible cage”, he explains of the US presidency. On the coffee table I spot a magnifying glass, a book on Jack the Ripper and an ashtray with “Hello C***y” written on it.

This rented house is where Depp had been living for months but he knows that he has to move. Somebody of his infamy simply cannot live near Carnaby Street without getting stuck indoors. “I can be isolated and happier than a clam,” he explains. “But I don’t get out much. I’m stuck with my thoughts; just thinking, writing or watching weird shit on YouTube. It can’t be healthy.”

Has he tried using a disguise? “I’ve tried hats,” he says. “Or I can grow a beard. But there is never any way to hide, and I just feel uncomfortable causing this weird form of attention I do, because I’m really shy.”

How is that compatible with his career? “Well, fame is the last thing I ever chased,” Depp says with a sigh. “If you look at the 9,000 years that I’ve been doing this shit, it’s pretty clear that I wasn’t ever thinking how I could be more famous, make a hit or please the press. Fame is an occupational hazard – but if I spout off about how upset I am, people will say, ‘Sweetheart, take a job pulling trash bags.’ ”

I spot a painting behind him – Depp is an artist as much as an actor these days, with a collection of 780 prints flogged for £3 million ($6.8m) through a London gallery in 2022. “This is a portrait of my daughter, Lily-Rose,” he says softly. Lily-Rose, born in 1999, and Jack, 2002, are the children Depp had with the French actress and singer Vanessa Paradis, his girlfriend of 14 years. The couple split up in 2012. In the painting she stares intently, blonde hair ruffled. “I never finished it,” Depp says. “She was 10 then, and 25 now.” Lily-Rose is an actress — she got excellent reviews in December for her role in Nosferatu.

“Years get away from us, don’t they?” Depp says. “How old are your kids?” Ten and eight. “Oh, I envy you. I’m of the empty-nest syndrome ” Does he miss having the children about? “Oh man, my kids growing up in the south of France in their youth?” Depp says of the estate he shared with Paradis. “I was Papa. I cannot tell you how much I loved being Papa.” Later the family moved to Los Angeles. “Then, suddenly, Papa was out the window. I was Dad. But Papa was awesome and I’m getting old enough for Papa to possibly come back. Some motherf***er’s going to have to call me Papa!” He pauses, quite clearly a man who would like to be a grandfather.

I ask him where home is. “Well, I don’t spend much time in the US. So there is the joint in the Bahamas or here. But home” He takes a lengthy beat. “Truly, the first time I felt I had a home was the place in the south of France where Vanessa and I raised the kiddies. That’s the only place that ever felt like home.”

In September last year I saw Depp at the San Sebastian International Film Festival for the premiere of Modi. Depp likes the Basque town: in 2021 the festival gave him a prestigious Donostia award for lifetime achievement at the height of his “boycott” and stuck with him throughout what he tells me later were “all the hit pieces, the bullshit”. He wants to repay them: on his last day in the town Depp dresses up as Captain Jack Sparrow to visit children at the local Donostia University Hospital. (He repeated the stunt last week at a children’s hospital in Madrid.)

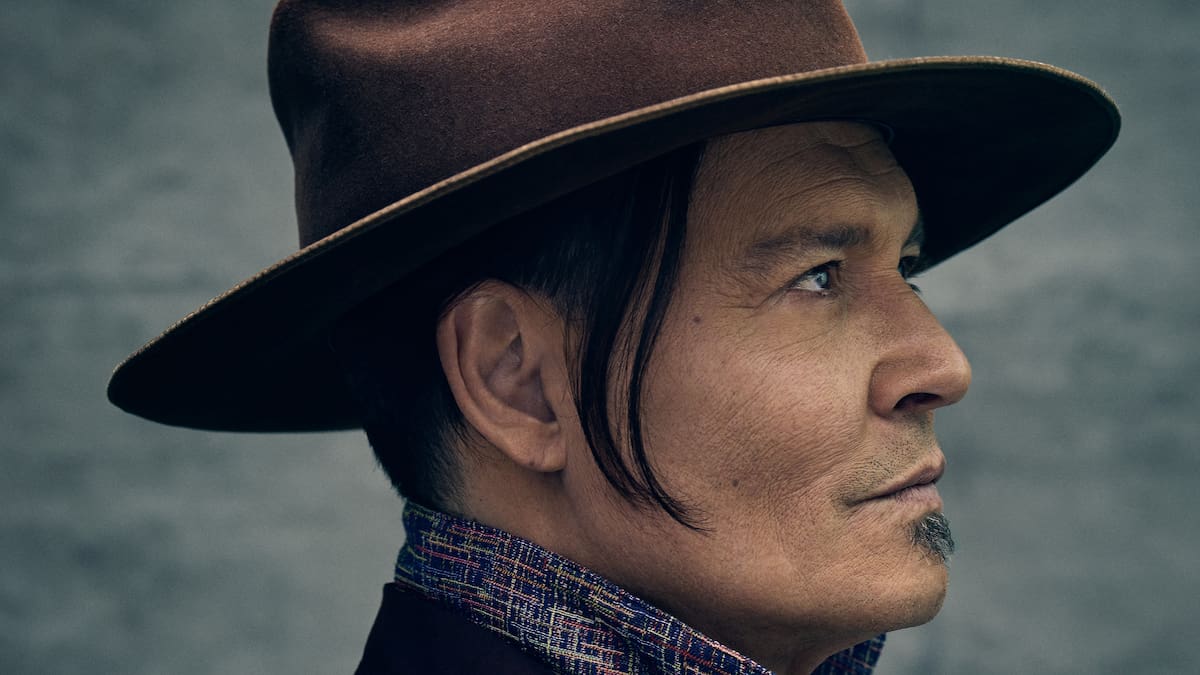

At the premiere crowds of intrigued locals and devoted Depp fans head to San Sebastian’s main cinema, the Kursaal – it is a cool, clear night and screams come from all around, even across the river. Depp remains a huge draw and people gasp as they glimpse him, in his brown jacket, floral scarf and broad-brimmed hat. He waves, signs autographs. A woman yells out, “Beautiful people!” as Depp takes his seat for his film.

The immersive and surreal Modi plays out like a fever dream, as Modigliani (Riccardo Scamarcio) scuttles drunk around Paris while a gaggle of friends and art dealers, including Stephen Graham and Al Pacino, either help or hinder his artistic greatness. Depp as a director has an eye for detail and eccentricity, while the script is rather blunt. Two standout lines are “Don’t kill the artist!” and “Nothing left to judge!”, while there is a volatile central love affair with a couple throwing objects at each other. I have never come out of a biopic and learnt so little about its subject but so much about its director.

Depp met the American actress Amber Heard in 2009, on the set of The Rum Diary, a film based on the Hunter S Thompson novel. Depp was 45, Heard was 22. At the time Depp was still in a relationship with Paradis. Depp and Heard married in February 2015, but by May 2016 Heard had filed for divorce and a restraining order, plus US$50,000 ($83,000) a month, claiming Depp had been “verbally and physically abusive”. By that August a settlement had been reached in which Depp agreed to pay Heard US$7m ($11.5m), which the actress said would go to charities.

In a joint statement the ex-couple said their relationship was “bound by love there was never any intent of physical or emotional harm”.

Then, in 2018, The Sun newspaper ran an article labelling Depp a “wife beater” that led him to sue its executive editor, Dan Wooton, and its publisher, News Group Newspapers, for libel at the High Court in London. He lost in November 2020, with Mr Justice Nicol stating, “The great majority of alleged assaults of Ms Heard by Mr Depp have been proved” – a decision that led to the so-called boycott of Depp as evidence detailed allegations of drug use, blackouts, abuse and a time when Depp claims Heard, or her friend, defecated in his bed.

Soon came further acrimony, as the media circus moved to the US. Specifically to a court in Fairfax County, Virginia, when, in March 2019, Depp sued Heard for libel over a column she wrote in The Washington Post in December 2018 headlined “I spoke up against sexual violence – and faced our culture’s wrath”. The trial eventually started in April 2022, with Depp attempting to prove that Heard was actually the one who had violently abused him.

The case was live streamed, peaking at 3.5 million viewers. On social media the fallout was bleak – mostly for Heard at the hands of Depp’s passionate fans and, some allege, bots. In June 2022 the jury found in favour of Depp, saying he was a victim of defamation and awarding him about $15m ($25m) in damages.

As the evening draws in, up in Depp’s living room conversation turns to the trial. He takes a break to visit the lavatory as more drinks are poured and I accept a glass of his own-brand rum – a nice drop, deep flavour.

What a tawdry affair that trial was – and not just the faeces. It was photos of Depp allegedly passed out; his “mega pint” of wine; a severed finger; Heard’s claim that he conducted a “cavity search” on her while looking for his drugs; Depp’s A-lister exes Kate Moss, Winona Ryder and Paradis backing him in court statements.

So much, literally, dirty laundry aired in public and I never really understood why Depp brought these cases to court. Surely, I say, he must regret the details that the public became privy to?

“Look, it had gone far enough,” he says firmly. “I knew I’d have to semi-eviscerate myself. Everyone was saying, ‘It’ll go away!’ But I can’t trust that. What will go away? The fiction pawned around the f***ing globe? No it won’t. If I don’t try to represent the truth it will be like I’ve actually committed the acts I am accused of. And my kids will have to live with it. Their kids. Kids that I’ve met in hospitals. So the night before the trial in Virginia I didn’t feel nervous. If you don’t have to memorise lines, if you’re just speaking the truth? Roll the dice.”

His voice has risen, shaking. He fiddles with a cigarette paper. “Look, none of this was going be easy, but I didn’t care. I thought, ‘I’ll fight until the bitter f***ing end.’ And if I end up pumping gas? That’s all right. I’ve done that before.”

I get that – and to many the second trial did what Depp wanted. Without its verdict it is unlikely he would be having this revival. However, when he talks about this period of his life and how he was wronged, I can’t help but think of Heard. After the trial in Virginia, while one juror said that “there wasn’t enough or any evidence that really supported what she was saying”, he also said that “they were both abusive to each other”. And what was abundantly clear during both trials was that Heard, a woman with far less money and significantly fewer fans than Depp, suffered more in both court and the court of public opinion than he did.

I saw that at his London trial. The mainly female crowd outside the court stayed there for weeks to wave at Depp and scream death threats at Heard. She used to be his wife. She was, I tell him, somebody that he had been in love with – surely it cannot have been easy to witness what she was going through?

“Well, that is the thing,” he says slowly, obliquely. “ ‘That I had been in love with ’ That’s where we could start, to look at the roots of ‘in love with’.” He makes an unexpected jump back to his childhood. “Because with regards to how I was raised, I wouldn’t say it was a house without love, but it was an intense love and I would not say that myself, or my siblings, or my pop and mom, experienced any great love or bliss.”

Depp was born on June 9, 1963, in Owensboro, Kentucky, a sizeable sprawl of middle-class city on the banks of the Ohio River. The family moved a lot before settling in Florida. Depp’s mother, Betty Sue, was a waitress, while his father, John, was an engineer. They divorced when Depp was 15, but scars were formed before then. Depp is the youngest of four – sisters Debbie and Christi and his beloved brother, Daniel – and it was not a happy home.

“My brother had his problems with the parents,” Depp explains. “There were many episodes of conflict – he and my father would duke it out – and Debbie had her problems with them too. Then Danny got married. Soon Debbie got married too, so it was only me and Christi. Then Christi got married, so it was only me. And dynamics changed. It was almost as if I was used to conflict. It was not abnormal. I did my best to just step in and out.”

The room falls silent for the first time.

“So,” he continues, veering back to his trial and Heard, “what were my initial dealings with what we call ‘love’? Clearly obtuse. And what that means is, if you’re a sucker like I am, sometimes you look in a person’s eye and see some sadness, some lonely thing and you feel you can help that person.

“But no good deed goes unpunished,” he says. “Because there are those who, when you try to love and help them, will start to give you an understanding of what that malaise, that perturbance was in their eyes. It manifests itself in other ways. And the interesting thing is that it is merely a sliver of my life I have chosen to explore, because it is my mother and my father. Do you know what I’m saying?”

Well, not entirely, but it seems Depp is talking about how he felt drawn to Heard because he saw in their relationship something similar to what his father shared with his mother. I let him continue.

“So Betty Sue was an awesome woman who revealed herself to be kind in the end, though she didn’t know how to treat anyone when I was growing up.” Depp’s mother died in 2016, aged 81.

“She liked to escape from reality from time to time and learnt how to live in a miserable state. I was in dreadful fear of this woman as a child but, at the same time, I loved her. So I’m not surprised I allowed myself to experience something – in some little psychological sphere – to help understand what it was like between my parents. I had to understand how my father dealt with it.

“So it would be dumb for me to carry any bitterness,” he continues. “Eternal hatred? You want to put curses on someone? No. I know who I am, what that was and, look, it was a learning experience.”

Yet the version of Depp who was adored in the public eye in 2009 is very different, to some, to the Depp of today. Still no regrets? “No,” he says sternly, the victor enjoying his spoils. “I have no regrets about anything – because, truly, what can we do about last week’s dinner? Not a f***ing thing.”

On a stifling day in Manhattan last September, Depp is putting the finishing touches to an exhibition of his art called A Bunch of Stuff. Later there will be an opening night party, attended by two titans who represent the two sides of Depp’s resurgent career – the indie film director Jim Jarmusch, who cast him in Dead Man in 1995, and the super-producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who ran the billion-dollar Pirates of the Caribbean franchise.

Depp is on a wander, passing comments to his team, who are busy creating various forms of content. He has paint splattered on his hands and, occasionally, he picks up and strums an acoustic guitar. A patch on his jacket reads “Take no shit”.

We amble through the gallery, an ad hoc space in a 1930s building in Chelsea. There are a lot of skulls and skeletons. In one vast immersive room his voiceover drolly if dolefully tells his story while cartoons are projected on to the walls around us. The voiceover intones how, as a child, Depp only went home to change his clothes because, if he stayed any longer, he would be hit by either a stiletto or an ashtray. “I felt like I was inside the actor’s brain,” is how one reviewer succinctly describes the show.

I spot a painting called Death by Confetti, a pensive-looking skeleton in front of brightly coloured dots. As I take it in I think of Depp’s voiceover in the adjacent room. It talks about Hollywood and how the industry builds you up, before letting you choke on the celebration, the confetti. “In the end you die,” goes the recording of Depp. “You actually die.”

As a child Depp found escape, not through acting, but music. His brother was the biggest influence, teaching him to listen to less Frampton Comes Alive, more Van Morrison. “Music was all I did from age 12,” he says. “I found my purpose.” Even at that young age Depp was gigging in the punk rock clubs of South Beach Miami where “people usually just go to score”. Was he still at school? “By 15 I didn’t see anything worth sticking around there for,” he says. “I wasn’t dumb but I just knew I wasn’t going to be an accountant.”

Did his teachers support his decision? “Yes! When I first dropped out I kept thinking about all the chicks I’d see in the hallways that I had crushes on, like this chick Renee. So I went back to my high school and said I wanted to come back. You see, my choices were the Marine Corps or going back to school.”

And you were worried about a lack of girls in the Marines? “Sure. Also I was irreverent in the face of authority. Once in biology I wasn’t listening and the teacher said, ‘Mr Depp, answer the question.’ I said, ‘What question?’ And he said, ‘What’s the difference between sexual and asexual?’ And I said, ‘Well, one’s from behind.’ That was not long before I dropped out. The principal said, ‘John, I know you play music. I know your dream. I strongly suggest you just follow that.’ ”

In 1983 Depp drove to LA with his band the Kids, later renamed Six Gun Method. He wanted to be a rock star but the band broke up. A few months later, in 1984, he found himself up for a small role in Wes Craven’s seminal horror film A Nightmare on Elm Street. “I didn’t know what I was doing,” Depp says. “And it was strange I got the role, because it was written for an athletic type, but this was early 1984, so I was white as a sheet, skinny, gaunt and tattooed.”

Three years after that he was cast as the lead in 21 Jump Street, the hit TV series about cops going undercover in schools. It changed everything. Depp was a star now, an actor by accident, something he was so uncomfortable with that he once defaced a billboard featuring his character, Officer Hanson.

“I was so miserable doing Jump Street,” Depp says. “I mean, I was lucky as a bastard, but it was uncomfortable. It was around then people started whispering when I walked in a room. This image is cultivated that you can’t control.”

How did he deal with fame? “Well, to this day I just rarely go out,” he says, rolling out one of his loud, lengthy guffaws. “If friends invite me out for Mexican, I say, ‘Dude, that’s sweet of you but I will ruin your night.’ My presence will bring attention and, Jesus, I have had almost 40 years of fame but I’m still not used to it. And I’m glad I’m not.”

What advice does he give to Lily-Rose? He smiles. “Sometimes kids say to me, ‘I want to be an actor, what’s your advice?’ And I say, ‘Don’t be!’ I know what’s coming for them. I was chucked on that road and the only advice that I can give is, ‘Don’t allow anyone to make you something you are not.’ They’ll want you to be a poster boy and it’s tempting — a lot of money. And if that’s the direction you want? Go for it. But don’t let anybody choose for you.”

Hence his CV of oddballs, with Jack Sparrow his only definitively mainstream part. As a child Depp loved the Three Stooges, Abbott and Costello and Tex Avery, and admired the 1970s counterculture entertainers Andy Kaufman and Richard Pryor. You can see this inspiration in Modi – “I love the timing, rhythm, madness.”

“And that’s my legacy, right?” he continues. “My films. That is what I ended up with after 40 years of making faces. And my kiddies will live with that legacy as well – they’ll have to carry my legacy with them once I hit the skids.”

Which brings us back to the Heard trials and how people he worked with spoke out against him. While talking about Heard he is imprecise; when it comes to the film industry he is clear and evidently furious about the Hollywood power-players who jumped off what they considered a sinking ship. His ire for them is bubbling, passionate. Take, for instance, his agent Tracey Jacobs. She signed Depp in 1988 and made them both millions before he sacked her in 2016, reportedly citing financial concerns. In deposition in the Heard trial, Jacobs claimed some studios had become “reluctant to use” Depp because of his tardiness on set. Depp disagrees.

“As weird as I am, certain things can be trusted,” he argues. “And my loyalty is the last thing anybody could question. I was with one agent for 30 years, but she spoke in court about how difficult I was. That’s death by confetti, these fake motherf***ers who lie to you, celebrate you, say all sorts of horror behind your back, yet keep the money – that confetti machine going – because what do they want? Dough.

“I’ll tell you what hurts,” he continues. “There are people, and I’m thinking of three, who did me dirty. Those people were at my kids’ parties. Throwing them in the air. And, look, I understand people who could not stand up [for me], because the most frightening thing to them was making the right choice. I was pre-MeToo. I was like a crash test dummy for MeToo. It was before Harvey Weinstein.” Heard’s accusations came a year before the producer’s fall from power. “And I sponged it, took it all in. And so I wanted from the hundreds of people I’ve met in that industry to see who was playing it safe.” He pauses. “Better go woke!” he hisses.

By the end of the night it’s as if Depp simply wants some company. He breaks out a bottle of red wine – given that he used to spend more than US$30,000 ($49,500) a month on wine, I gladly accept a glass. He proudly shows me a first edition he bought of Arthur Rimbaud’s poem Est-elle Almée? from 1872.

Then he shares the music he loves via his laptop and a Bluetooth speaker. First, a cover of Bob Dylan’s Girl from the North Country that he recorded with Marcus Mumford of Mumford & Sons in Los Angeles. He says he loves the Dublin rock band Fontaines DC. He wonders what the odds are on his old friends in Oasis lasting an entire tour: “Noel is funny as f*** and I saw Liam at Glastonbury a few years ago and he was positive, cool and sweet, which was great to see, because I remember another Liam from many years ago.” He mentions the guitarist Jeff Beck, who formed a band with Depp in his final years and died in 2023: “He was my best friend.”

Depp clearly prefers the company of musicians, spinning yarns about Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love, and the time when he and Kate Moss went to St Barts in the Caribbean – “That’s what Kate liked to do!” – and were struggling to figure out the lyrics to the just released REM song Find the River. In a bind, Depp simply phoned up Michael Stipe, REM’s singer, over speakerphone.

Conversation meanders and opinions tumble out – a few juicy ones that he takes off the record, which given what else he is happy to say indicates quite how juicy they are. He laments a boom in reality TV, in which “some f***ing guy from f***ing Podunk, Iowa, can get his own show” and worries what quick-grab fame has done to a generation. “Not necessarily all those kids stuck the landing particularly well.” He sighs, a man who belongs to a bygone era, when Hollywood made movie stars, not franchises and memes. “There was a quality of person – comedian, actor. They were unique, you know?”

Depp is going to miss this old London home. After we meet he heads off to shoot Day Drinker and he knows he is about to be reintroduced to the world. But it seems like a world that he feels out of step from. “I’ve a deep appreciation for times gone by,” he says. “There was simplicity, certain kinds of inherent moral, ethical standards.” And he thinks that has changed? “Yes, for the most part.” He talks about the dark wooden floorboards under our feet and all the people who have walked them over the centuries. And he talks about this quite sadly, in a way that suggests the past is where he would like to be.

Written by: Jonathan Dean

The Sunday Times Magazine/ News Licensing

© The Times of London