The Western Pacific Region is facing a significant measles outbreak, marked by a sharp rise in reported cases across multiple countries, including those in Asia, the Pacific, the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand.

This resurgence underscores critical immunization gaps and highlights the urgent need to strengthen public health interventions.

Meanwhile as of Friday 16 May 2025, Papua New Guinea (PNG) has confirmed a polio outbreak—the first since 2018—after detecting two cases of poliovirus type 2 in children from Lae, Morobe Province.

Environmental samples from Port Moresby also tested positive for the virus, indicating community transmission. Genetic sequencing links the strain to poliovirus circulating in Indonesia.

The Ministry of Health and Medical Services (MHMS) in partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, are working closely together to ensure the protection and safety of every Solomon Islander from these diseases.

Get to know measles and polio

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease. It remains an important cause of death among young children globally, despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine. Measles is transmitted via droplets from the nose, mouth or throat of infected persons.

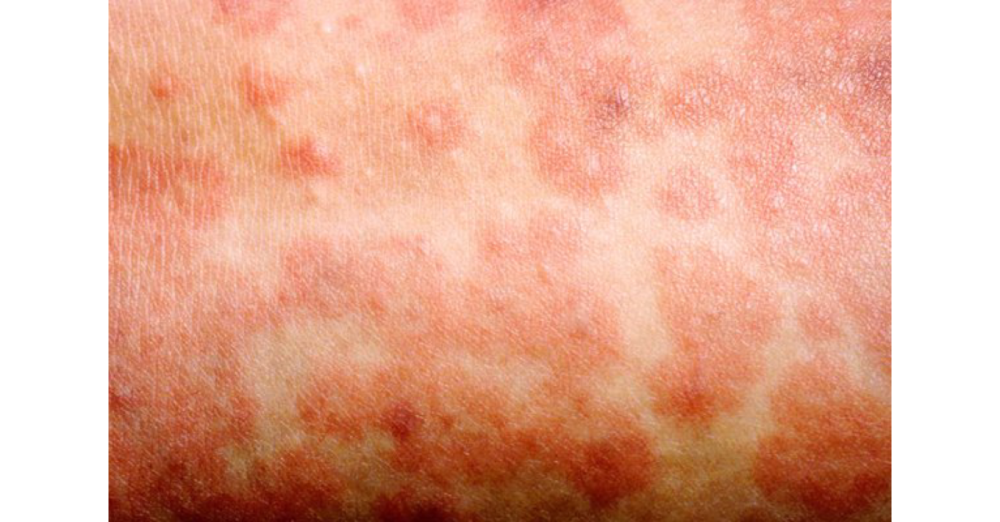

Initial symptoms, usually appear 10–14 days after infection and include high fever, a runny nose, bloodshot eyes, and tiny white spots on the inside of the mouth. Several days later, a rash develops, starting on the face and upper neck and gradually spreading downwards.

Polio is an equally highly infectious viral disease. It mostly affects children under 5 years of age.

The virus is transmitted by person-to-person spread mainly through the faecal-oral route or, less frequently, by contaminated water or food and multiplies in the intestine, from where it can invade the nervous system and cause paralysis and, in some cases, death. Symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, vomiting, stiffness in the neck, and pain in the limbs that usually last for 2 – 10 days.

Who is vulnerable?

Any non-immune person (not vaccinated or vaccinated but did not develop immunity) can become infected. Unvaccinated young children and pregnant persons are at highest risk of severe measles complications.

Children with malnutrition or other causes of a weak immune system are at highest risk of death from measles.

Being vaccinated is the best way to prevent getting sick with measles or spreading it to other people. Community-wide vaccination is the most effective way to prevent measles. All children should be vaccinated against measles. The measles vaccine has been in use since the 1960s. It is safe, effective and inexpensive and Parents, churches, communities as frontline protectors.

The MHMS calls upon parents and guardians to proactively look after the health of children, especially those at risk, who may be unvaccinated or under-vaccinated. It is everyone’s responsibility to ensure that every child remains safe from measles. Vaccines are free, safe and available at the health clinics in the country.

Aside from parents, local leaders, churches, and youth groups are encouraged to spread the message about early signs of measles, encourage families to complete both MR vaccine doses, and help families reach clinics for check-ups and immunizations.

Communities can also launch nationwide information campaigns about the dangers of measles and the benefits of immunization and engage local leaders, churches, youth groups, and traditional authorities to build and sustain vaccine trust and dispel misinformation. Moreover, community participation can be promoted in vaccination days through SMS, radio, and village announcements.

What’s being done

To better protect the population, the MHMS has implemented effective systems for surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD). This proactive approach ensures early detection of outbreaks and swift action to contain vulnerabilities within communities. Regular updates on the status of VPD will be communicated to the public to promote transparency and trust.

WHO continues to provide on-the-job coaching to frontline health workers focused on improving VPD surveillance. These coaching sessions aim to strengthen the capacity of healthcare staff in timely case detection, accurate classification, and comprehensive reporting of suspected VPD cases, including measles. This ongoing support helps reinforce early warning systems and ensure prompt public health responses.

Meanwhile, UNICEF has scheduled a workshop with church leaders as part of its ongoing community engagement strategy. During this workshop, the Health Promotion team will sensitize and empower the religious leaders with key information about measles, its modes of transmission, associated health risks, and the importance of timely vaccination. By engaging trusted community figures, the initiative aims to amplify advocacy efforts, dispel misinformation, and increase public confidence in the immunization program.

Measles and polio coverage in Solomon Islands

Measles-Rubella (MR) coverage in the Solomon Islands currently stands at 70.1% for the first dose and 60.6% for the second dose – far below the WHO-recommended 95% threshold required to prevent outbreaks. This suboptimal coverage creates pockets of vulnerability, particularly among children under five and those living in remote island communities.

In 2014, the Solomon Islands experienced a significant measles outbreak, reporting nearly 5,000 suspected cases and nine confirmed deaths. The outbreak began in June, following the return of a traveler from Papua New Guinea, and rapidly spread across all ten provinces, within densely populated areas such as Honiara, Guadalcanal, and Malaita being the most affected.

The 2014 measles outbreak in the Solomon Islands highlighted the importance of maintaining high routine immunization coverage and conducting periodic SIAs to address immunity gaps. It also emphasized the need for robust surveillance systems, effective communication strategies, and logistical preparedness to respond swiftly to outbreaks. The experience underscored the critical role of coordinated efforts between national health authorities and in-country partners in managing public health emergencies.

Meanwhile, polio vaccination coverage in the Solomon Islands shows moderate success but remains below optimal levels. The first dose of oral polio vaccine (OPV) has 88.2% coverage, while the third dose drops to 82.7%, indicating issues with completing the full schedule. Inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) coverage stands at 84.1%.

While these figures are relatively high, they fall short of the >95% threshold recommended by WHO to prevent outbreaks, creating an immunity gap.

This gap arises from incomplete vaccination and suboptimal IPV uptake. Children who do not receive the full OPV series are at risk of inadequate protection, and low IPV coverage compromises systemic immunity, which is crucial in the transition away from OPV use. These shortfalls increase the risk of vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) and potential outbreaks, especially in remote or underserved communities with poor sanitation or high mobility.

– MHMS