A remote Amazon tribe has slammed “unfounded” and “untrue” reports that claimed the arrival of the internet led to some of its men becoming addicted to porn.

Earlier this month, The New York Times published an article describing how Brazil’s 2000-member Marubo tribe had been left bitterly divided by the arrival of the Elon Musk’s Starlink service last year, which connected the remote rainforest community along the Ituí River to the web for the first time.

The piece, by journalist Jack Nicas, painted a picture of a community grappling with both the positives — such as access to health information in emergencies and video chats with loves ones — and negatives.

“When it arrived, everyone was happy,” said Tsainama Marubo, 73. “But now, things have gotten worse. Young people have gotten lazy because of the internet. They’re learning the ways of the white people.”

Nicas wrote, “After only nine months with Starlink, the Marubo are already grappling with the same challenges that have racked American households for years: teenagers glued to phones; group chats full of gossip; addictive social networks; online strangers; violent video games; scams; misinformation; and minors watching pornography.”

Alfredo Marubo (all Marubo use the same last name), leader of a Marubo association of villages, was one of the most vocal critics of the internet, warning he feared the tribe’s oral traditions and knowledge would be lost.

“Everyone is so connected that sometimes they don’t even talk to their own family,” he said.

Nicas wrote, “He is most unsettled by the pornography. He said young men were sharing explicit videos in group chats, a stunning development for a culture that frowns on kissing in public.”

Alfredo said elders were “worried young people are going to want to try it”, referring to the graphic sex depicted in the videos, adding some leaders had ”told him they had already observed more aggressive sexual behaviour from young men”, The New York Times article stated.

After the article was published, new outlets around the world ran stories quoting The New York Times with headlines suggesting the arrival of the internet had caused the tribe to become “addicted to porn” and social media.

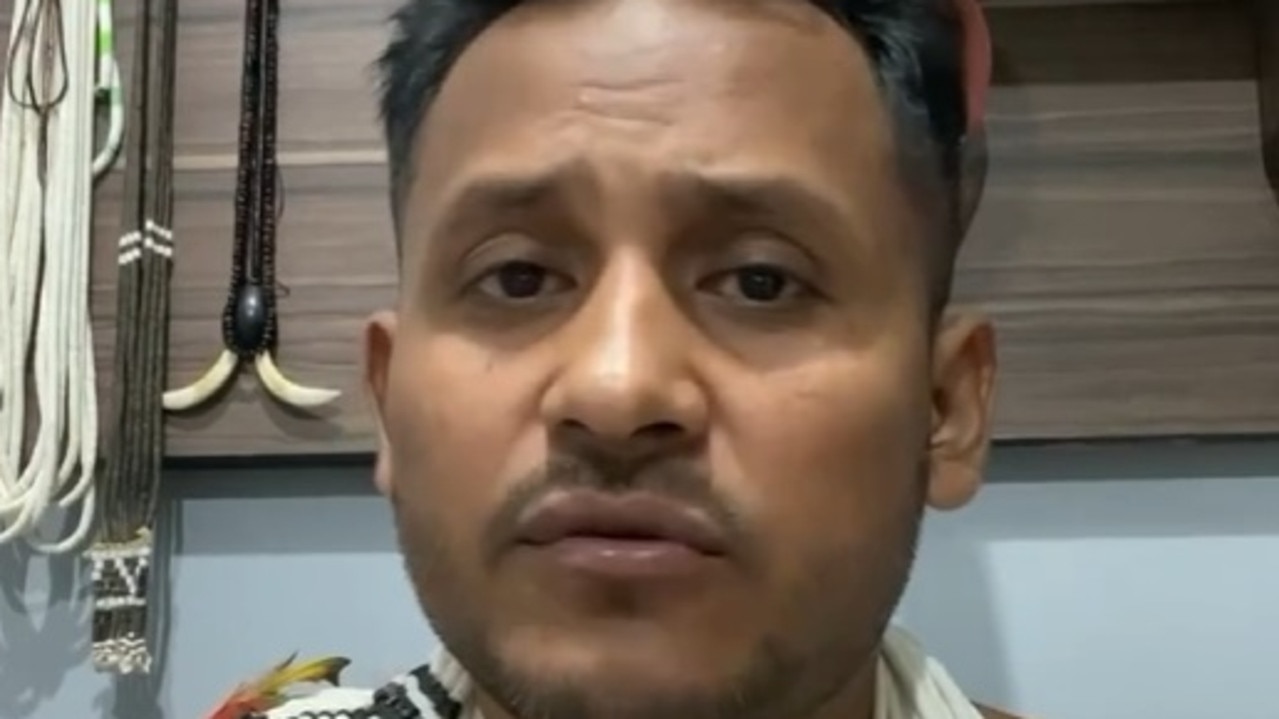

But Enoque Marubo, 40, the Marubo leader who brought Starlink to his tribe’s villages — and bitter rival of Alfredo — published a scathing video on Instagram on Sunday night blasting the headlines as “fake news”.

“I am here to repudiate the fake news that has been circulating around the world in the last week, alleging that the entry of the internet into our communities has resulted in addiction to pornography,” he said.

“These statements are unfounded, false and only reflect a biased ideological current that disrespects our autonomy and identity.”

Enoque said the Marubo had been kept as a “showcase” for the world for more than a century but “this bubble should no longer exist”.

“We want our autonomy and we are tired of the violation of our rights,” he said.

“Unfortunately, the recent report by The New York Times highlighted more of the negative aspects, which resulted in the dissemination of a distorted and damaging view. The New York Times reporter actually was with us to cover this. In the middle of the forest he was treated with great respect. I don’t know why he followed this distorted line which resulted in this fake news. I want to reiterate the repudiation [of] all these publications of unfounded lies that appeared on the internet.”

Enoque again stressed that the internet was “a very important tool” for the Marubo.

“Internet saves lives — that would be enough,” he said. “It facilitates communication with distant relatives, assists teachers in the classroom, allows communication quickly between communities. It is also a very important tool for our territorial security.”

He finished by slamming “non-Indigenous or white people” trying to “decide for us” what is best.

“It hurts us, disrespects us, disrespects Indigenous peoples,” he said.

“This ethnocentric thinking in relation to Indigenous peoples needs to end … and you need to understand that Indigenous peoples have the capacity, like non-Indigenous people, to make decisions. This guarantees our autonomy. This must be respected.”

Alfredo, the one to raise concerns in the original article about pornography, released a statement on Tuesday saying the misleading headlines “have the potential to cause irreversible damage to people’s image, and therefore we feel exposed in the face of this misinterpretation of the accurate reporting”.

The New York Times, for its part, has pointed the finger at other media outlets for making “sensationalist headlines” out of its reporting.

“No, a remote Amazon tribe did not get addicted to porn,” read the newspaper’s follow-up headline on Monday.

Nicas wrote that his original piece featured some elders who “complained of teenagers glued to phones, group chats full of gossip and minors who watched pornography”, but that “after publication, that angle took on a whole different dimension”.

“Over the past week, more than 100 websites around the world have published headlines that falsely claim the Marubo have become addicted to porn,” he said.

“The Marubo people are not addicted to pornography. There was no hint of this in the forest, and there was no suggestion of it in The New York Times’ article.”

Mr Musk also weighed in. “It was disrespectful and unkind of The New York Times to say that about the tribe,” the Starlink founder wrote on X.

Starlink works by connecting antennas to 6000 low-orbiting satellites. The necessary antennas were donated to the tribe by American entrepreneur Allyson Reneau.

Initially, the internet was heralded as a positive for the remote tribe who were able to quickly contact authorities for help with emergencies, including potentially deadly snake bites.

“It’s already saved lives,” Enoque stated in the original article.

Members are also able to share educational resources with other Amazonian tribes and connect with friends and family who now live elsewhere.

It has also opened up a world of possibilities for young Marubo, some of whom have been unable to conceptualise what lays beyond their immediate surrounds.

One teen told The New York Times that she now dreams of travelling the world, while another says she aspires to become a dentist in Sao Paulo.

However, Enoque also complained of the significant downsides.

“It changed the routine so much that it was detrimental,” he stated. “In the village, if you don’t hunt, fish and plant, you don’t eat.”

“Some young people maintain our traditions,” TamaSay Marubo, 42, added. “Others just want to spend the whole afternoon on their phones.”

Tribespeople became so addicted that Marubo leaders, fearing that history and culture — which is passed down orally — could be lost forever, they have now limited access to the internet for two hours each morning, five hours each evening, and all day Sunday.

But parents still worry the damage may already be done.

Another father, Kâipa Marubo, said he’s anxious about his children playing violent first-person shooter games.

“I’m worried that they’re suddenly going to want to mimic them,” he stated.

Meanwhile, others say that they’ve fallen victim to internet scams given that they lack digital literacy, while many youngsters are chatting with strangers on social media.

Flora Dutra, a Brazilian activist who works with indigenous tribes, was instrumental in helping connect the Marubo to the internet.

She believes anxieties about the internet are inflated, and asserts that most tribespeople “wanted and deserved” access to the world wide web.

Still, some officials in Brazil have criticised the rollout to the remote communities, saying special cultures and customs could now be lost forever.

“This is called ethnocentrism,” Ms Dutra said of such critiques. “The white man thinking they know what’s best.”

— with NY Post