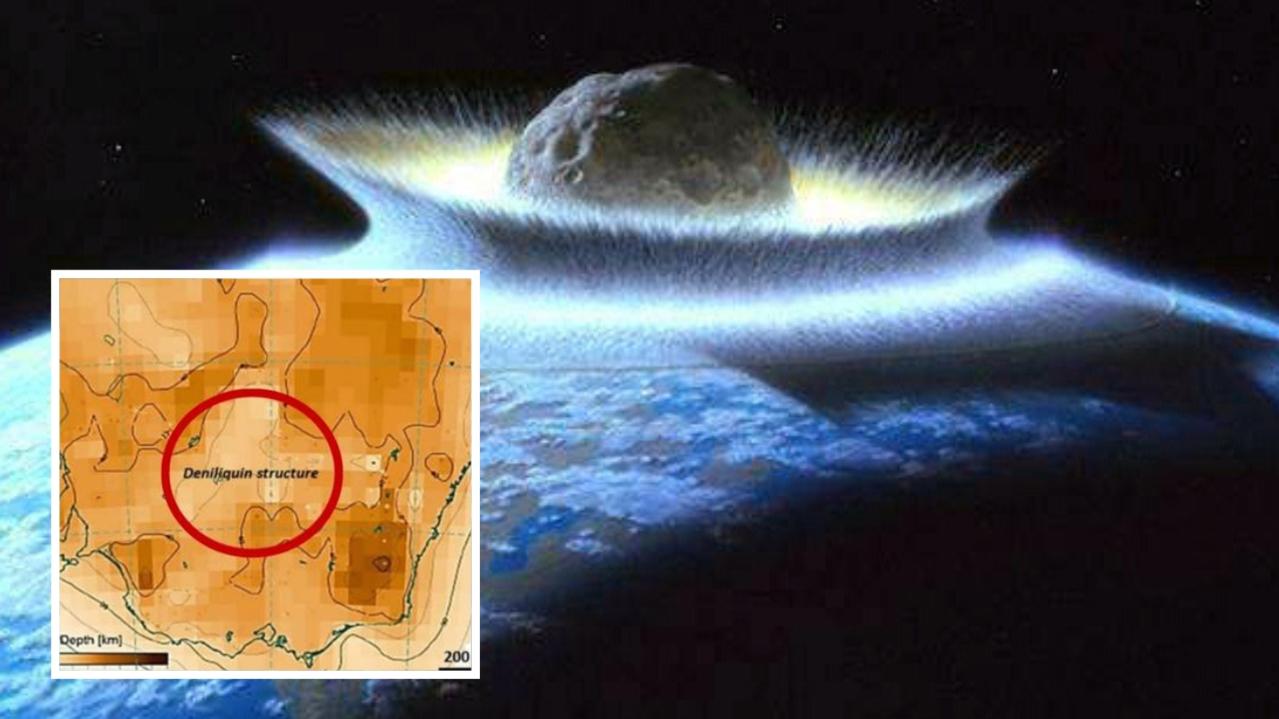

Experts believe the Australian continent is hiding the largest meteor crater on Earth, revealing a hit at least twice as powerful as the one that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Recent research published in the journal Technophysics points to the world’s largest known impact structure, buried deep in the earth in southern NSW.

Australia is home to at least 38 confirmed and 43 potential impact structures after it was pummelled by asteroids in Earth’s early history, but the Deniliquin structure is by far the biggest.

The structure, which is yet to be further tested by drilling, spans up to 520 kilometres in diameter, making it three times as wide as Mexico’s Chicxulub crater, which was left by the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Asteroid that left crater likely wiped out 85% of life

Like many large meteor craters, the structure hiding under NSW is believed to be tied to a mass extinction event.

The Deniliquin structure was likely located on the eastern part of the Gondwana supercontinent before it split apart into many smaller continents, including Australia.

Researchers believe the impact that caused the structure may have occurred during the Late Ordovician extinction event, which wiped out 85 per cent of life on Earth between 445.2 and 443.8 million years ago.

That impact was more than double the scale of the Chicxulub impact, which killed off the dinosaurs.

It’s also possible the structure is even older, according to study co-author Andrew Glikson. It may be tied to the Cambrian era, which occurred about 514 million years ago.

Why are impact craters difficult to spot?

Earth has been hit by massive asteroids many times in its long history, but the impacts of these hits are often difficult to see for several reasons.

The first is erosion. When an asteroid strikes, it leaves behind a crater with an uplifted core, “similar to how a drop of water splashes upward from a transient crater when you drop a pebble in a pool”, Dr Glikson recently explained in LiveScience.

That central uplifted dome is a key characteristic of impact structures, but it can erode over millions of years and become difficult to identify.

Impact structures can also be buried by sediment over time, or they may disappear as a result of subduction, wherein tectonic plates collide and slide under one another and change the Earth’s crust.

How did scientists find the crater?

Between 1995 and 2000, scientist and fellow study co-author Tony Yeates suggested magnetic patterns beneath the Murray Basin in NSW pointed to a massive, buried impact structure.

Analysis of the region between 2015 and 2020 then revealed the existence of a 520-kilometre-wide structure with a seismically defined dome at its centre — much like the structures that are found after an asteroid strikes.

The Deniliquin structure has all the features that are expected from a large impact structure. Magnetic readings of the area reveal a symmetrical rippling pattern in the Earth’s crust around the crater’s core, which was likely formed in the immense heat after the asteroid hit. The readings also show “radial faults”, or fractures that splinter out from the centre of a large impact structure.

“Currently, the bulk of the evidence for the Deniliquin impact is based on geophysical data obtained from the surface,” Dr Glikson wrote.

“For proof of impact, we’ll need to collect physical evidence of shock, which can only come from drilling deep into the structure.”

“The next step will be to gather samples to determine the structure’s exact age,” he added.

“This will require drilling a deep hole into its magnetic centre and dating the extracted material.”